Picture this: you’re on your 30 minute lunch break, unsure what you should do.

Where are you? You’re walking out of the sticky tacky office building that houses your less-than-living wage 9-5 day job, slightly recoiling from the sunshine. You decide to drive to that $14 salad place with the $16 left in your bank account but you keep getting Slack notifications from your boss. You mark yourself as unavailable when you notice that you have the red circle of life/death hovering over your other gig’s scheduling app.

You tell yourself to just answer it once you’re out of the car, but the traffic light’s red.

What are you gonna do? Just sit there?

The Good, The Bad, The Productive.

Can’t-stop-won’t-stop, rise and grind, getting the bag/bread, work hard, play hard: we are defined as a culture that considers “busy” an admirable personality trait. This is the age of productivity. But, what is it?

Basically, productivity is the amount of any commodity created in a certain period of time. So, how many papers you edit per hour, how many tables you move during a shift, how many sales you make in a day.

Initially, the concept of productivity was just another economic metric of a worker’s output and the subsequent profit made. It started out as, and continues to be, a main character under capitalism, measuring how much you can produce in as little time as possible. Outside of work, how productive you were with your day wasn’t really up for discussion.

This places us in its present-day silhouette: productivity as not only an economic unit of measurement, but a social pressure. Working the dictated 40 hours per week and calling it a day is obsolete. Now, you simply move from one work space to the next and are expected to use each minute you have to produce.

The new normal means having multiple gigs because one job isn’t enough to pay the bills. You can’t really leave your work place at the end of the day because you’re still getting e-mails from a co-worker or text messages from a manager trying to schedule you for a 6 AM shift at 3 AM the same day. Or, your couch is your desk, in which case you will never see the light of day.

Is anybody out there? Photo by Beth J via Unsplash

Self-care is great, but when you finally have a chance to do it, you find yourself instagramming the whole thing in a subconscious attempt to prove that even though you’re not “working”, you’re still producing something: “free time”. Here’s the proof of it; don’t worry y’all, I’m not doing nothing! You find yourself just as tired as you were before.

We’ve been force-fed one of capitalism’s fundamental economic concepts and created a home for it within our psyche.

The Internalization of Productivity.

In an interview, author Malcolm Harris, of the book “Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials”, states: “…We’ve internalized this drive to produce as much as we can for as little as possible. That means we take on the costs of training ourselves (including student debt), we take on the costs of managing ourselves as freelancers or contract workers, because that’s what capital is looking for.”

An integral aspect of capitalism is, really frankly, how well can you sell yourself: what can you produce? How much of it? How long will it take you? What will it cost me? What can I gain from it?

Pointedly, this has been taken a step further. It’s not enough to work a full day, only to go work at least half of the night, but now you have to be passionately engaged with your labor. Your work can’t just feed and shelter you, but now it has to fulfill you.

Cue the sadly/hilariously memed modern interview process whenever you’re asked on the 14th page of the job application: “Tell us, why do you want to work here?”

Time to get gone.

The current reality of an economy whose minimum wage is nowhere near a livable wage and your ability to survive hinges on working either multiple jobs or ridiculous hours, combined with the social pressure of not only maintaining a near-constant state of busy-ness but attributing your self-worth to your work and how full your calendar is leads to the internalization of productivity. Let alone the fact that this disparity only increases depending on your race and gender, a typical occurrence under this framework. I know, long sentence.

So, what happens when this drive to validate yourself through what you externally produce is internalized by a generation(s)?

You create a culture of burn out.

This is Your Brain On Productivity.

A study at the University of Michigan by Jennifer Crocker, PhD, found that college students who base their self-worth on external sources like “academic performance, appearance, and approval from others reported more stress, anger, academic problems, relationship conflicts, higher levels of alcohol and drug use, and increased symptoms of eating disorders.”

The study also found that students who based their self-worth on internal sources “felt better, received higher grades, and were less likely to use drugs and alcohol, or develop eating disorders.”

Additionally, “college students who based their self-worth on academic performance did not receive higher grades despite being highly motivated and studying more hours each week than students who did not rate academic performance as important to their self-esteem.”

The amount we produce is marketed as an intrinsic part of who we are. This idea, also called workism, is the idea that work is central to your identity. Workism also includes the belief that “any policy to promote human welfare must always encourage more work.”

We’re encouraged by our bosses, by our peers, our family, the internet, and even coffee mugs to work more.

The coffee mug is no longer just for providing you with caffeine, but is a source of motivation. Also, a last minute gift for that person you kind of know. Photo by Kyle Glenn via Unsplash

While reaching a state of perfect balance is an impossible task, this extreme focus on work has to be taking a toll on our collective health, right?

In a 2018 survey, almost 40% of participants reported that they felt more anxious when compared to a year ago. It’s important to note that this already comes from a 36% increase in reported rates of anxiety between 2016 and 2017. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), anxiety disorders are the most common mental disorders in the world, with 1 in 13 people suffering from anxiety on a global scale.

In fact, Millennials and Gen Z are the most affected by mental health disorders to date, with a study that found a 63% increase in adults aged 18 to 25 who reported “symptoms of major depression” from 2009 to 2017. The same study also found a 52% increase in teens aged 12 to 17 from 2005 to 2007.

As always, it’s important to point out that this is only based on people who actively reported themselves as feeling anxious or depressed. But with the stigma surrounding mental health, it can be hard for a lot of people to admit that they have a mental illness. This number can, and likely is, significantly higher.

This doesn’t just end at an acknowledgment of work causing or exacerbating mental illness. In an interview with Jeffrey Pfeffer on his book “Dying for a Paycheck”, he discusses his study across 10 different workplaces and how they affected workers’ health.

After reviewing these workplaces in how they dealt with “economic insecurity, work-family conflict, long work hours, and absence of job control”, the study found that these work practices make up for approximately “120,000 excess deaths a year in the United States, which would make the workplace the fifth leading cause of death.” Death, y’all.

As the surprised dog stares into the void, we find ourselves wondering: is this worth it?

There are a number of factors that play into anxiety and other mental illness, including brain chemistry and the traumas that you’ve experienced. But in a world that tells you to focus all of your energy, attention, and identity on how productive you are, is it such a stretch to say that the way we work is contributing to our rising rates of unwellness?

That maybe the way we work is, well, bad for us?

Bad News: Your Increased Productivity is Not Really Reaching Your Wallet.

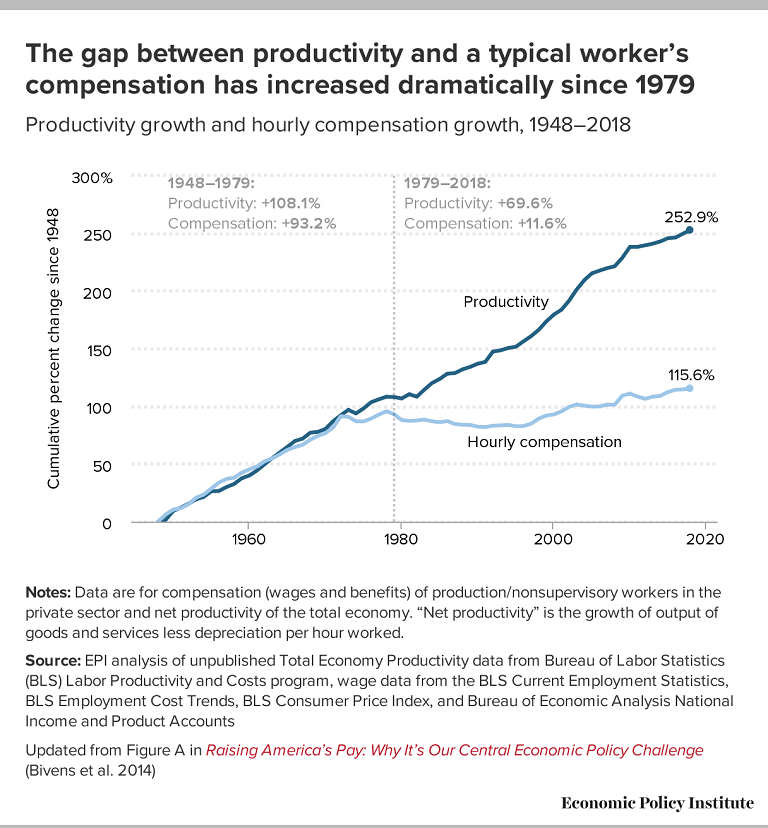

All of this work isn’t really adding up to more in our pockets. The numbers show that from 1979 to 2018, net productivity rose 69.6% while the hourly pay of the average worker increased only 11.6% in this same 29 year range. And yeah, this was adjusted for inflation.

While rates of productivity have continued to rise, our compensation has stagnated. Could it still be all that avocado toast causing this? Via EPI

Another study analyzing trends between productivity and wage even found that wages (adjusted for inflation) rose 1.8% from 2000 to 2014, while net productivity rose 21.6% in that same time frame.

The same study even found that despite the increase in productivity offering the potential for increased wages for most workers, any chance of this actually happening was stomped out by rising inequality.

@f.aa.ded

If we’re doing all of this work, for no real increase in compensation for what we’re doing…what are we doing?

Is This Work Worth It?

I think it’s pretty clear: the way we work is not working. We’re burning out (play, Mitski’s “A Burning Hill”), we’re not compensated fairly, we’re not allowed to take a nap unless we vlog about taking a nap.

Frankly, I don’t think you should be required to bend over backwards for a boss or a paycheck in order to survive or thrive, especially at the expense of your own health- which let’s be honest, is usually the case.

If we spend most of our waking and should-be-sleeping hours working with the idea of just funding your life, what life are you actually paying for? It seems more and more like our paychecks are only giving us just enough to keep us coming back in the next morning, but not much else. What if there’s more to life just outside of our job’s parking lot?

So You’ve Internalized Productivity: Now What?

You are more than your external output for the day. Snooze your notifications once you’ve had enough (or even if you haven’t), or better yet, set a time in the day to retire your phone. Hide your day planner for a week and disappear into the night. Make goals that don’t even remotely relate to what you do for money (i.e., nap for at least 2 hours: check). If you are in a position to quit your particularly back-breaking job, here’s the sign from the universe that you were looking for. Take up a hobby that has no productive outcome.

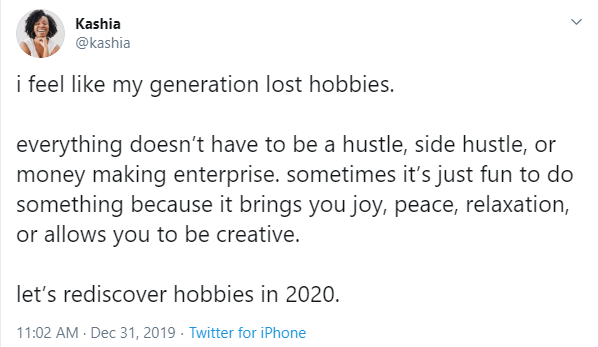

Hobbies in 2020! For no reason other than having fun! A concept! Via @Kashia on Twitter

All of these things listed above are great, and if you can, I highly recommend any and every maneuver you can do for yourself in order to subvert the way you are having to live in order to, well, live. But it’s important to note at this point that capitalism creates the conditions that make it difficult to use your time in ways that are meaningful to you. After you’re (finally) done working, it’s hard to find the energy to do anything other than decompress from work. And placing your phone on “Do not Disturb” isn’t going to “cure” the problem.

For the real, systemic change that is needed to fix the problem that capitalism has created, the way we work has to change. Before the trolls emerge to say that this is impossible, change has been effected in the past lil ol’ things like child labor laws and the implementation of the 8 hour work day, to name a few.

An article by The Atlantic discusses this current M.O. under late capitalism in detail: the absurdity of the way we are currently being forced to live our lives and the fact that this framework is making less and less sense with each day.

But, it also touches on the perspective that moving on to a new way of existing doesn’t have to be scary. Instead, this is full of potential. The future of the way you choose to engage with your life can be whatever you want it to be, provided you’re ready to fight for it.

Take a second to picture it. A life where you’re not forced to decide between your health or paying your rent. The existence of choice.

Imagine that.